Reviews of Alan Alda's Books

If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look On My Face?

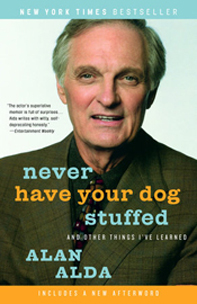

Things I Overheard While Talking to Myself | Never Have Your Dog Stuffed

Reviews of New York Times Best Selling Book

If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look On My Face?

My adventures in the art and science of relating and communicating

Forbes:

“Alda uses his trademark humor and a well-honed ability to get to the point, to help us all learn how to leverage the better communicator inside each of us.”

Kirkus Review:

"A distinguished actor and communication expert shows how to avoid 'the snags of misunderstanding' that plague verbal interactions between human beings...A sharp and informative guide to communication."

"A distinguished actor and communication expert shows how to avoid 'the snags of misunderstanding' that plague verbal interactions between human beings...A sharp and informative guide to communication."

Kirkus Review:

"A distinguished actor and communication expert shows how to avoid 'the snags of misunderstanding' that plague verbal interactions between human beings.

When Alda (Things I Overheard While Talking to Myself, 2007, etc.) first began hosting the PBS series Scientific American Frontiers in 1993, he had no idea how much the job would change his life. In the 20 years that followed, he developed an enduring fascination with 'trying to figure out what makes communication work.' As a TV show host who interviewed scientists and engineers, Alda became painfully aware of his own shortcomings as a communicator and how his background as an actor could help him improve. In the first section of the book, he discusses how effective communication requires listening with ears, eyes, and feelings wide open. Drawing from research, interactions with science professionals, and his work as an actor, Alda reveals how individuals who aren't 'naturally good' communicators can learn to become more adept by practicing their overall relating skills. He describes activities like the 'mirror exercise,' in which partners observe and mimic each other's actions and speech. Not only do people learn how to focus on each other, but they also 'strengthen cohesion and promote cooperation' in groups. In the second section, Alda, who founded the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University, points out the importance of empathy in communication. He discusses, among others, an exercise that forced him to name the feelings he saw others express. Raising awareness of emotion increases empathy levels, which can trigger the release of oxytocin, the feel-good 'love hormone.' By adding emotion to communication, using storytelling, avoiding jargon, and eliminating the assumption that others share the same knowledge base, message senders can forge closer bonds with recipients. The book's major strength comes from Alda's choice to take an interprofessional approach and avoid offering prescriptive methods to enhance interpersonal understanding. As he writes, communication 'is a dance we learn by trusting ourselves to take the leap, not by mechanically following a set of rules.'

A sharp and informative guide to communication."

Close

BookPleasures.com:

"This book goes past simply paying attention and being alert to the people we come into contact with. It teaches us how we can see and read emotions with great accuracy via practice, how to be more empathetic and understanding, how to pick up on non-verbal cues regardless of gender, deciphering the real messages between one another, and more. All of these techniques can get us better results as communicators and listeners..."

BookPleasures.com:

"Alan Alda, author of If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look on my Face? is a huge Hollywood actor. Alan has won Emmy’s, an Academy Award, written and directed numerous films (The Aviator) and PBS series, as well as, starred on Broadway. (2017) He is one of my favorite television and movie personalities and I am honored to read and review his book. He loves science and has helped scientists, engineers, and other professionals learn how to communicate with the everyday people through his groundbreaking studies in communication and lessons on what does and does not work. For years he was the darling doctor, Hawkeye Pierce, on the television series M.A.S.H.. He has been on numerous other televisions series as guest actor and was in 2014 named fellow of the American Physical Society. Alan is a visiting professor at Stony Brook University in their communications department.

Alan Alda talks about how he felt he knew how to communicate pretty well from his acting experience and his comedy improve training. However, as he embarked on his PBS television series Scientific American Frontiers, The Human Spark, and Trial he learned what little he knew on the topic of communication. This sparked his thirst to learn all he could about the dynamics of human interaction and communication which is the basis for this book.

Alan considers his first television interview on Scientific America with a man who developed solar panels with a tinge of guilt for not doing his homework beforehand and for not understanding completely what this show might entail. However, he learned a lot from that experience and moved on to become an incredible interviewer and custodian for the world of science and how best to communicate those sometimes difficult to understand terms and concepts to the regular viewer so they can find as much delight and inspiration as the scientist and engineer do.

This book is filled with time tested communication games and examples to help move groups of unconnected people toward active listening and true understanding of what is being said. The spoken word is filled with subtle and sometimes not so subtle cues that can teach us what we hope to learn or befuddle us beyond our wildest dreams. IT should be the express desire of all of us to become the best communicators we can be.

This book goes past simply paying attention and being alert to the people we come into contact with. It teaches us how we can see and read emotions with great accuracy via practice, how to be more empathetic and understanding, how to pick up on non-verbal cues regardless of gender, deciphering the real messages between one another, and more. All of these techniques can get us better results as communicators and listeners.

I taught Business Communication to junior and senior level students at the University of Memphis in Memphis, TN and would have enjoyed using some of these games to help my students become more adept at the art of and science behind communication. I enjoyed this book and believe you will too!"

--Michelle Kaye Malsbury

Close

The Gold Foundation:

"In this marvelous book...Alda co-creates for the willing reader a sense of intimacy, of kitchen table conversation (at the table of an incessantly curious, well-read and down-to-earth host). Like most excellent conversations, Alda’s book is not linear and is packed with stories. Many of the stories come from the extensive interviews he has done with scientists through his work as the host of Scientific American Frontiers and the Founder of the Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University. But he brings you with him on other adventures as well..."

The Gold Foundation:

"Alan Alda begins his latest book in the midst of a conversation with the reader. His title “If I Understood You, Would I have this Look on my Face?” seems to be the response to a question you have just asked. Before you have time to argue that you’ve never even met him before, you begin to wonder: “Is he annoyed? Teasing me? Or perhaps he is posing an authentically curious question?”

You examine the cover image (a wonderful cartoon by Barry Blitt) to decipher his facial expression and body language. Alda greets you with an open visage with raised brows, a barely perceptible smile, facing palms at shoulder height simultaneously welcome you in and convey a sort of “who knows?” gesture. He has just made the point, reinforced in moving and delightful ways throughout the book, that communication is more than words, more than tone of voice, more than body language, always somewhat ambiguous, and something that a person cannot do alone.

In this marvelous book subtitled My Adventures in the Art and Science of Relating and Communicating, Alda co-creates for the willing reader a sense of intimacy, of kitchen table conversation (at the table of an incessantly curious, well-read and down-to-earth host). Like most excellent conversations, Alda’s book is not linear and is packed with stories. Many of the stories come from the extensive interviews he has done with scientists through his work as the host of Scientific American Frontiers and the Founder of the Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University. But he brings you with him on other adventures as well.

You are with him in the chair of a defensive dentist, you cringe as he cuts his hand grappling with a hermetically sealed package (the product of poor communication between the marketing and sales divisions of a company), you walk with a young Alda selling mutual funds, most doors closing in his face until he realizes that sales are about figuring out what the other person is interested in. Day to day life, it seems, is packed with opportunities to observe, decipher and improve our relationships.

Alda humbly shares his own communication snafus – resulting in annoyed scientists and a bored grandson. He travels round and round the Kolb learning cycle – experiencing, reflecting, refining and taking what he learns back onto the conversational road. He shows us that relating is context dependent and requires the practical wisdom to know how best to communicate in this situation with these people.

Much of Alda’s book hinges on two concepts- Empathy and Theory of Mind. The former is the “feeling with” another human being which is necessary for authentic relating; the latter refers to our developmentally honed detective skills which enable us to discern what another person may be thinking and feeling by observing clues in body language, tone of voice, or particular word choice. He features Gold Foundation grant recipient Helen Riess’ work on the science and teaching of empathy. The works he cites are so varied and compelling that I wish he had included a reference list for further exploration.

Alda’s book implies that much of what we commonly do in medical education to teach communication skills could be done more effectively. Every medical student knows the feeling of being an imposter; wearing your starched white costume and reciting the script of a doctor and wondering if you will ever stop feeling like you’re acting. Who would have thought that one way to feel less like an actor is to do more of what real actors do?

Alda describes the way in which actors learn to relate through improvisational exercises. What would happen if we gave our students instructions to communicate bad news in gibberish so as to isolate our body language and tone of voice from our words, or to co-create a relational experience with a peer through mirroring each other’s motions? Most of the doctors I know view their bodies as a convenient vehicle to move their brains from place to place. Alda invites us into wholeness, to engage our entire bodies, all our senses. He asks that we take a close look at our use of technical language and ingrained habits of communication that may bind us to each other but separate us from patients and non-medical colleagues. Learning to communicate would be much easier if we didn’t need to unlearn so much!

And for you healthcare trainees and professionals who think “relating” is the icing on the cake of medical practice, Alda has news for you. It’s not the icing on the cake. It’s the cake!"

--Elizabeth Gaufberg, MD

Close

JournalingOnPaper.com:

"This book is a down-to-Earth look at how we as humans need to do better at communicating, and how exactly we can accomplish this goal. I highly recommend it to anyone who wants to do better in the office, at school, or at any relationship..."

JournalingOnPaper.com:

"Communication is an art form. We may think we are getting our message through to others, but invariably what the world hears is very different from what we had hoped to convey. Without a doubt, this is problematic in so many ways that we need to ask if individuals can fix that glitch in our interpersonal relationships? The answer is yes, but….but it takes understanding and above all, work. The question is how do we get better at making others understand us? Well the book, If I Understood You, Would I have This Look on my Face? is a great place to start.

Part memoir and part how to manual, the author, Alan Alda, yes that Alan Alda of MASH Hawkeye fame, takes us on his personal journey of discovery and education in simply learning how to talk to other people. The book is written in such a way as to make it all very self explanatory. He begins, at the beginning of his quest, by giving us a history lesson of when he simply realized that the words used in every day discourse can be confusing, frustrating, and have their entire meaning wholly misinterpreted.

He takes us through his educational adventure, and scientific meanderings. He introduces us to some of the more prominent researchers in the communication field, and lets us in on some very interesting experiments. Alda teaches us about the concepts of contagious, active listening, empathy and theory of mind. Ideas and tools well known to any of us in the autism community, but not always as easily explained. Every idea, every exercise, every step forward is broken down into understandable parts so that the average reader can employ these same drills at home. He begins his communication lessons with engineers and teaching scientists how to talk to the average person. Not surprisingly, they needed a lot of work with interpersonal communication skills.

Whether he is explaining the use of improvisation in helping communication, mirror exercises, or the notion of commonality, Alda regales us with his own missteps and successes. It is strangely gratifying and helpful to read how he garnered an understanding of his own failings, and was able to overcome his own communication failures. Of course, the reader can find that funny, as Alan Alda among many things, is an award winning actor/ comedian, who without the ability to communicate properly could have not have had such an exemplary career. Yet that is exactly what occurred. Mr. Alda is refreshingly honest about his own blind spots even to the very end of the book.

This book is a down-to-Earth look at how we as humans need to do better at communicating, and how exactly we can accomplish this goal. I highly recommend it to anyone who wants to do better in the office, at school, or at any relationship. Personally, I think it definitely will come in handy if you have a recalcitrant teenager at home as well. Well, at least I am hoping it does…."

Close

BookLoons.com:

"As one would expect, Alda communicates his topic clearly, with humor, wit and catchy comparisons... I devoured this volume in one sitting and look forward to another..."

BookLoons.com:

"Alan Alda has long been my hero, not only for enriching our lives with M*A*S*H's Hawkeye, but also for writing Never Have Your Dog Stuffed and Things I Overheard While Talking to Myself. Now he takes his host of fans into the realm of science (and what it - and improv acting - say about our attempts at communication) in If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look on My Face?: My Adventures in the Art and Science of Relating and Communicating.

As one would expect, Alda communicates his topic clearly, with humor, wit and catchy comparisons. The quote at the beginning of the book sums it all up well - 'The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.' The book is divided into two main parts - Relating is Everything and Getting Better at Reading Others - and exercises (that the author has tested) to improve communication are mentioned throughout.

Alda tells us that 'Developing empathy and learning to recognize what the other person is thinking are both essential to good communication, and are what this book is about.' He proceeds to explain how and why. Much of his understanding grew from his experience as an actor and also his involvement with the PBS show, Scientific American Frontiers, in which he had to communicate directly with scientists and draw from them explanations that laymen would understand and connect with. On the show he learned contagious listening.

He tells us how improv exercises help engineers communicate their work; how mirroring can improve cooperation and trust between individuals; how the presence of women in a group enhances teamwork; the importance of expressing Yes And (acceptance and deep listening); and how too much information can be detrimental to getting key ideas across. And its not all upbeat - Alda also conveys the downside of dark empathy, and the pros and cons of jargon.

The chapter I enjoyed most, Story and the Brain, speaks to the importance of story to mankind, in both communication and memory. And Alda ends his book on a humorous note with a self-deprecating account of poor communication with a grandchild. I devoured this volume in one sitting and look forward to another - perhaps Mr. Alda could apply his excellent communication skills to explain global warming to the unenlightened, and give all our grandkids a future."

Close

Jaquo.com:

"This is a truly fascinating book...which is brilliantly written and makes even the more tricky concepts easy to understand, is invaluable for anyone, no matter what their walk of life..."

Jaquo.com:

"Yes, that Alan Alda. Hawkeye. M*A*S*H.

When this book landed on the review desk at JAQUO HQ my immediate thought was ‘Alan Alda – must be well worth reading’. Then I saw the tag line under the title – My Adventures in the Art and Science of Relating and Communication. Hmm. Well…

But then I remembered the great title – If I Understood You Would I Have This Look on My Face? Yes, I decided, this would be worth reading and oh boy, was I right!

This is a truly fascinating book and the first surprise was the fact that communication has been a serious interest for the actor for many years. But maybe it’s not so surprising because that’s exactly what an actor does – communicates. But this book, which is brilliantly written and makes even the more tricky concepts easy to understand, is invaluable for anyone, no matter what their walk of life.

The chances are strong that whoever we are, we can encounter difficulties in understanding others and being understood. Do we truly relate to people as well as we could?

- Do you understand your partner?

- Could your relationship be improved if communications were enhanced?

- If you’re a doctor, can you relate well to your patients?

- Can parents find an easier way to communicate with their children?

- Can business people and salespersons become more successful using the techniques in this book?

- Teachers, do your students relate well to you? Do you to them?

- Writers – can you really empathise with your readers and understand what they are looking for from you?

- And of course, bearing in mind the author, can you become a better actor by improving your communication skills?

- Plus, we’re asked the tantalising question – can we learn to read minds?

This book isn’t only full of practical advice, case studies and easy-to-read data – it also is full of memorable quotes. My favourite – right now – is ‘The trouble with a lecture is that it answers questions that haven’t been asked‘.

Think about that. Do you lecture your teenagers about why they should be home before midnight? When you’re berating your partner for not doing the dishes, are you lecturing him/her? Yes, this book applies to everyone in any walk of life, not just teachers, scientists, doctors and business people – the ones who we tend to think about when we consider lectures.

For some reason, this book made me think of Prince Charles who, many years ago, wrote about his concern for our planet and the environment. He could have quoted many statistics and obscure figures about the damage we are doing to our world. In fact, he may have done but all I remember from his book is the following quote regarding conservation.

I don’t want to be confronted by my future grandchild and have them say ‘Why didn’t you do something?

This was quite a few years ago but I remember the quote well. It relates. It communicates the point without rhetoric or statistics. It’s a sentence that everyone can understand. It says so much in one sentence. Has the future king of England ever met Alan Alda and discovered his techniques? It seems so!

Truly though, I highly recommend this book to everyone. We might believe that we are wonderful communicators, or that we relate to other people.

Or we might feel that ‘at our age’ we ‘know it all’ and have nothing to learn about relationships and communication. (By the way, Alan Alda was born in 1936.) I’d love you to read this book and see how it can improve your life in so many ways."

--Jackie Jackson

Close

BookReporter.com:

"...thought-provoking guide that can be used by all of us, in every aspect of our lives --- with our friends, lovers and families, with our doctors, in business settings and beyond."

BookReporter.com:

"Alan Alda, the award-winning actor and bestselling author, tells us the fascinating story of his quest to learn how to communicate better, and to teach others to do the same. With his trademark humor and candor, he explores how to develop empathy as the key factor.

Alan Alda has been on a decades-long journey to discover new ways to help people communicate and relate to one another more effectively. IF I UNDERSTOOD YOU, WOULD I HAVE THIS LOOK ON MY FACE? is the warm, witty and informative chronicle of how Alda found inspiration in everything from cutting-edge science to classic acting methods. His search began when he was host of PBS’s 'Scientific American Frontiers,' where he interviewed thousands of scientists and developed a knack for helping them communicate complex ideas in ways a wide audience could understand --- and Alda wondered if those techniques held a clue to better communication for the rest of us.

In his wry and wise voice, Alda reflects on moments of miscommunication in his own life, when an absence of understanding resulted in problems both big and small. He guides us through his discoveries, showing how communication can be improved through learning to relate to the other person: listening with our eyes, looking for clues in another’s face, using the power of a compelling story, avoiding jargon, and reading another person so well that you become “in sync” with them, and know what they are thinking and feeling --- especially when you’re talking about the hard stuff.

Drawing on improvisation training, theater and storytelling techniques from a life of acting, and with insights from recent scientific studies, Alda describes ways we can build empathy, nurture our innate mind-reading abilities, and improve the way we relate and talk with others. Exploring empathy-boosting games and exercises, IF I UNDERSTOOD YOU is a funny, thought-provoking guide that can be used by all of us, in every aspect of our lives --- with our friends, lovers and families, with our doctors, in business settings and beyond."

Close

Science20.com:

"Like the book, he is funny or deep from one minute to the next...he is in the running for greatest scientist interviewer of all time."

Science20.com:

"You are about to hear a huge sigh of relief from the entire science journalism community, because Alan Alda, a man who can interview E.O. Wilson and Jim Watson with ease, who hosted the terrific Scientific American Frontiers, and founded the Alan Alda Center for Communication Science at Stony Brook University, has trouble communicating.

You wouldn't think so. It certainly surprised me. The second time I met Alda was at the Geffen Theater in Los Angeles a few years ago, where he was putting on his play about Marie Curie ("Radiance: The Passion of Marie Curie"); his favorite scientist, he said. I went there to interview him and we had lunch in one of their stately lounge rooms and I mentioned I was working on my first book and asked him how many drafts he had done of the play and he replied he stopped counting around 70, because they weren't major, so he started using A, B, etc.

Let that digest for a moment.

Seventy drafts is not what you expect from someone who doesn't feel like they don't know how to communicate. Or maybe it is. If you feel like you have a vague sort of "impostor syndrome" (I do - and if you are a science writer and say you don't, you are only fooling yourself) you are going to work hard to get it right. Before any interview I have ever done, I have prepared a great deal because the last thing I want is someone rolling their eyes. A journalist friend of mine, Greg Critser, tells the story of being sent to interview physicist and Nobel laureate Murray Gell-Mann and promptly being thrown out. As Critser said in hindsight, Gell-Mann also did something a good communicator will do. He told a young arrogant journalist, who thought he was doing a scientist a favor and giving them 'free publicity', exactly what he had done wrong, and when he could come back.

I've done that since. Interviewing someone I consider a gifted communicator like Alda, there was no point in false modesty. I plainly told him that, given his ability to as an interviewer, if he felt like he needed to answer the question I should be asking instead of the one I did, to go ahead and do so. He laughed. Who knew inside he was just as worried about being able to keep up with me?

Well, he is, and that is one of the great things about learning from someone who will do the work to explain why communication is so difficult. Like Critser, he didn't know it was difficult. He was confident - at first. Making a huge blunder right away is the surest way to calibrate your own expertise. And it helps to let the humor of things shine through when it's merited.

Laughter is the shortest distance between two people - Victor Borge

After reading his new book, If I Understood You, Would I Have this Look on My Face? My Adventures in the Art and Science of Relating and Communicating, you will have some sense of his anxiety as well. Even if I couldn't detect it. Why was it not apparent? Because I felt like he was so skilled at interviewing that even while being interviewed we didn't have an interview, we had a conversation.

Like the book, he is funny or deep from one minute to the next. He lays bare his beliefs, even when he knows they don't always jibe with what his more reductionist proclivities might entail. But this is not a woo self-help book for budding journalists. He notes how theory of mind and empathy have become new-age synonyms for faux sympathy. In the place of cloying platitudes we get brilliant insights from people he discusses, like, "And, ultimately, what emerged was that I helped her understand death--and she helped me understand how to be a better doctor".

Keep it simple. Three big ideas.

Everyone wants a take-home message, and it has that as well. You can get a more thorough understanding of it when you buy the book.

It all shows Alda has clearly grown as a communicator despite his impostor syndrome, to where he looks so comfortable he is in the running for greatest scientist interviewer of all time. What about the rest of us? I suppose we have to continue on our way. There's hope. A few weeks back I took a car back to the apartment I keep in Manhattan and the driver and I talked. At the end of the trip, he asked me, 'Are you a journalist?'

Some of the time, I replied, and why did he ask?

'Because you listen.'

So maybe I am halfway there."

--Hank Campbbell

Close

LAReviewOfBooks.org:

"The need is undeniable: people habitually experience communication breakdowns, which often involve failures of empathy. Whether they happen in bedrooms or boardrooms, they’re universally isolating..."

LAReviewOfBooks.org:

"THE ACTOR Alan Alda has a personal reason for being concerned about the art and science of communication. He was the victim of a dentist who didn’t bother explaining a procedure, leaving Alda with what he calls a “smilectomy.” Warily watching the scalpel head toward his mouth, the actor was in no position to object when the dentist in question removed his frenum, that bit of connective tissue that holds your upper lip to your gum and, among other things, allows you to smile.

Filming a movie a short while later, he was shocked when the director of photography asked him why he was sneering when he was supposed to be smiling. “I was smiling,” Alda insisted. “Nooo. Sneering,” said the director.

When Alda then smiled at himself in a mirror, his image sneered back. “Without my frenum,” he recounts, “my upper lip just hung there like a scalloped drape in the window of an old hotel.” The good news was that his new face 'enabled me to play a whole new set of villains.'

Which perhaps explains the title of his new book in more ways than one: If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look on My Face?

Alda’s unwitting makeover was a wakeup call to the damages done routinely by such encounters: “suffering the snags of misunderstanding […] is the grit in the gears of daily life,” he writes.

Known early in his career for comic turns in the classic series M*A*S*H and the romantic comedy The Four Seasons (which he also directed), and later as (sneering) bad guys in The West Wing and Crimes and Misdemeanors (among dozens of other films, TV shows, and stage appearances), Alda realized that his oblivious dentist — though looking at him intensely — was not “seeing” him at all. He wasn’t seeing him as a person, and, more to the point, as a person who made a living with his face — a face that sometimes needed to smile. The dentist saw removing the frenum, a procedure he had himself invented, as a clever way to pull a flap of gum tissue over the front tooth he had just extracted in order to increase the blood supply.

Our natural tendency not to notice what (or whom) is around us is, of course, vastly exacerbated by the various “devices” that so cunningly seduce us into electronic worlds much more controllable, tidy, and convenient than human ones. But even face to face, we’re remarkably adept at seeing right through or past each other. We see teeth, for instance, but not faces. We pay attention to tattoos and titles, the cars people drive and the schools they attended (or did not attend), and mostly we see their roles in relation to ourselves: my child, my boss, my mechanic, my student, my enemy, my doctor, my patient, the asshole who cut me off.

I suspect that’s one reason we’re so pleasantly surprised by those rare moments when others acknowledge our existence: that little wave from another driver that says, “You go on ahead,” followed by your nod, “I see you.” The “How are you?” at work from a person who actually waits for an answer. I recently saw a pickup truck driver cut off a taxi and then pull up to the window and apologize: “Sorry, I didn’t see you.” Wow.

Those sparks of connection remind us of just how much we miss when we tune people out. And failing to communicate goes far beyond just “grit in the gears.” “People are dying because we can’t communicate in ways that allow us to understand one another,” writes Alda. “That sounds like an exaggeration, but I don’t think it is.”

If anything, I’d argue that it’s an understatement. When we can’t communicate well enough to convince people to refrain from texting while driving, to vaccinate their children, to negotiate before shooting, then yes, people will die. When we can’t convince governments to fix faulty dams, stop violent people from buying guns, or take seriously the dangers of unsafe water, bad air, and climate change (for starters), yes, people will die.

Alda’s primary focus is science communication, a field whose gears he’s been greasing for decades. But recently his love of experiments, especially on himself, has led him to try something both silly and unreasonably effective: teaching improv to scientists. What he’s learned has led him to believe that improvisation (and related skills) can work as empathy enhancers that could help cure much of what ails us.

¤

Alda credits his 11-year stint as host of Scientific American Frontiers as his impetus for trying to figure out what makes communication work — or, in his case, initially not work. When shooting began in 1993, he dove into conversations with scientists without really paying attention — 'hearing without listening,' as Simon and Garfunkel would put it. He realized that his responses weren’t growing out of what other people were telling him. In one of my favorite lines from the book, Alda points out something we all know so well and heed so little: '[R]eal conversations can’t happen if listening is just my waiting for you to finish talking.'

Improv doesn’t allow that kind of pretend communication. As Alda knew from his long career in acting, improv forces you to pay close attention, observe barely perceptible inflections, notice not just voice but body language, and a million other subtle clues.

Full disclosure: I come briefly into the story here. As a science writer and fan of Scientific American Frontiers, I reached out to Alda, who had read and liked some of my books (my heart be still!); I invited him to USC, where I teach, to see how we might collaborate on communicating science. At dinner, a USC engineer asked: “Alan, what would you like to do?”

To everyone’s surprise, what he wanted to do was teach improv to a bunch of engineering students. In the book, he says I was skeptical of his experiment. The truth is, I thought he was nuts. But the Viterbi School of Engineering offered Alda its elegant boardroom for an entire afternoon, plus some 20 young engineers, faculty, refreshments, AV equipment, and anything else he needed. The young engineers gave presentations on their work, as Alda had requested. All used PowerPoint. All were stiff, and most were unintelligible. None took much notice of whether the audience was engaged or understood a word.

Then, for at least three hours, it was playtime. Early in Alda’s career, he’d taken a workshop with Paul Sills at Second City stage in New York, where he learned to rely on a book by Paul’s mother — Viola Spolin — titled Improvisation for the Theater. Full of games and exercises, this volume is the go-to resource for learning and practicing improv. It was the basis for our day. A tug of war with an imaginary rope forced us to pay close attention not simply to a physical object that didn’t exist, but also to the slightest movements, grunts, groans, sighs, and postures of people on the opposing team — and to respond in real time (or get pulled to the floor).

One group created an imaginary space out of their hands and bodies; they “built” it together by observing what other players were doing. 'If another player creates a bump in the sculpture, you don’t ignore it; you acknowledge the bump and build on it,' writes Alda. Others took on imaginary roles involving imaginary relationships with other people, who then had to guess what those relationships were — not by asking anything, but by behaving in a way that made sense in the imaginary context. At one point in the afternoon, someone started to play an imaginary trombone, and then, one player at a time, the young engineers created an imaginary orchestra.

'Communication doesn’t take place because you tell somebody something,' writes Alda. 'It takes place when you observe them closely and track their ability to follow you.' This sounds like a no-brainer. And yet, how many speakers in classrooms and lecture halls don’t even notice when audience members nod off, get lost in their laptops, or simply look pained or bored?

When we concluded our theater games, the students gave their presentations again. We were communally amazed. Abandoning their slides, they looked us in the eye. One self-conscious young woman who’d previously looked over our heads, and a young man who’d focused on his PowerPoint slides, now spoke directly to us, the audience. They remembered they were people speaking to other people. They engaged. They were present. I was especially impressed by a student who went from describing her research in a passive voice, as work conducted by parties existing only in the third person, to telling her personal story. It was almost as if she’d just discovered that her scientist self and her personal self were the same, and she had a story to tell.

After that, I started inviting improv teachers into my writing classes. Writing is based on noticing, after all. But it’s also very much about remembering the reader on the other side of your words, like the students on the other end of our imaginary rope in tug of war. Writing may be a lonely occupation, but writing that gets read is always a partnership.

¤

When Alda’s Scientific American TV series ended after an 11-year run, he delved more deeply into what he’d learned about communication, exploring the science behind it. Fascinated by how emotion enhances communication, he became interested in Theory of Mind (ToM), a subject he explored in his three-part PBS series The Human Spark. A big part of what makes humans different from most other animals is their ability to think about what someone else is thinking, feeling, wanting, fearing, or about to do — including what that someone else is thinking about what a third person is thinking about what that first person is thinking, and so on. This capacity is widely considered to be the basis for empathy.

Alda came to realize that the “curse of knowledge,” as he calls it, was a well-known phenomenon, and he cites studies confirming that “knowing” can be a disadvantage in trying to communicate. That’s because it’s so very hard to shake the feeling that if you know something, then other people must know it too. Worse, it becomes almost impossible even to imagine what it’s like not to know.

The 'curse of knowledge' helped explain why Alda’s early TV interviews had gone so wrong. He’d assumed he and the scientist were on the same page, thinking the same thoughts, and that he was asking the right questions because he’d done his homework. Fixed on the script in his own head, he was oblivious to the fact that the scientist might want to take their conversation in an entirely different direction. Knowing things, he thought, mattered more than simply listening. After a while, he began to go into interviews essentially unprepared, relying on the power of natural curiosity and honest ignorance. The conversations became more lively and informative for the actor, the scientist, and the audience alike.

'There’s another great cooperation killer,' he writes. 'The Sound of Certainty: the triumphant, but self-defeating, tone of voice that announces, I know what I’m talking about and that ends the discussion' (emphasis his).

In contrast, the kind of active listening required in improv means letting the other person know that you’ve heard what they said, either through your words or actions or both. This requirement is captured in improv’s 'Yes. And …' mantra: 'Yes, I hear you (see you). And this is what I’m doing with it.' As Alda writes, 'This process of allowing something you receive from another person to transform into something else is one of the most interesting experiences in improvising.' And in life.

¤

Our magical day with the Viterbi engineers helped solidify Alda’s conviction that he was onto something. But he also knew a one-shot wouldn’t have lasting effects, and so he wondered if he could do something more long term and systematic — like teaching improv to scientists on a regular basis. He approached the usual suspects, including the president of a university well known for its top-tier scientists. The president wasn’t interested: his university, he said, already gave a prize rewarding good communication. Alda pointed out that the award-winners were by definition already skilled. How about teaching those who weren’t? No luck.

Then, by chance, he found himself at dinner with Shirley Strum Kenny, the president of Stony Brook University on Long Island. Enthusiastic from the start, she rounded up people to help. Before long, Alda’s seed of an idea had grown into the Stony Brook Center for Communicating Science, which has since trained thousands of scientists in dozens of universities, laboratories, and medical centers throughout the world. In 2013, it was renamed the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science.

Improv is still at its core, but, of course, good communication requires more — for example, compelling storytelling. Human brains are wired to seek out narratives (or make them up) in just about anything. Alda quotes Aristotle saying that a story should have a beginning, a middle, and an end. But there’s a lot more to it, he reminds us: 'After all, a dead cat has a beginning, a middle, and an end.'

Not everyone gets to attend an improv class. So Alda wondered if there were improv skills people could acquire on their own. Could he teach people to increase empathy in a solitary, do-it-yourself context? The need is undeniable: people habitually experience communication breakdowns, which often involve failures of empathy. Whether they happen in bedrooms or boardrooms, they’re universally isolating. 'Not being able to communicate,' writes Alda, 'is the Siberia of everyday life.'

Not surprisingly, he decided to experiment on himself. Fully aware that his activities might be dismissed as a “mental aberration” rather than a proper scientific study, he nonetheless set out to see if he could systematically increase his ability to empathize. In the chapter 'My Life as a Lab Rat,' he tries a variety of approaches, including practicing reading the faces of people he runs into in taxis, stores, on the street, and trying to see the situation through their eyes.

On one such outing he became so empathetic with a New York taxi driver that when he heard it was the end of a long shift and the driver hadn’t had a chance to use a bathroom, Alda insisted the driver drop him off a few blocks from his destination (closer to the bathroom). They got into an empathy match: 'You’re a nice person,' the driver argued. 'I’m taking you to the door.'

'I couldn’t stop him,' writes Alda. 'This man was sacrificing his bladder for me. I wished I’d never started the whole thing.'

He stopped practicing empathy for a while. 'It was exhausting,' he concedes. He then tried again in a more focused manner: by simply labeling the emotions of people. It gave him a 'sense of comfort,' he writes, 'almost a sense of peace. […] Practicing contact with other people feels good. It’s not like lifting weights. It feels good while you’re doing it, not just after you stop.'

Alda recounted his experiences to a scientist friend who helps autistic kids, suggesting they test the principle. The scientist thought Alda’s teach-yourself-empathy idea was 'clever.' 'What a nice word,' writes Alda. 'I started to get excited.'

The scientist wired up Alda’s brain to an EEG to get a baseline empathy reading. Alas, a week of labeling emotions didn’t do much to improve his empathy score (actually, Alda did worse). Once he got over the disappointment, he took comfort in the idea that he could turn his experience into a story. 'This would be a helpful thing to do,' he writes. 'It would be a service to mankind. In other words, I was slightly depressed.'

¤

Despite the recent proliferation of Empathy Apps designed for all our devices (yes, that’s a real thing), relating to others will never be as simple as labeling emotions or clicking buttons — or even spending a day with an improv master. As author Sherry Turkle, director of the MIT Initiative on Technology and Self, told a USC audience in March, “The only real empathy app is yourself.”

Human connection has always been scary and hard. Technology, says Turkle, makes it easier than ever to keep our distance, making “us forget what we know about life.” Life, lived in-person and awake, is both messy and mined with communication traps. It’s also full of opportunities to connect in surprising ways. But we can’t see them when we’re not paying attention, not open to unexpected commonalities.

It’s hard not to see this as the reason so many progressives felt “Trumped” in the recent election. Yes, much about Trump is crazy and deplorable. But that doesn’t mean all his supporters are crazy or deplorable (or that there aren’t so-called crazy deplorables on the left). We didn’t see beyond their hats, or try to understand their fear of strange ideas, or their anger at being left out and left behind.

Firmly in the grasp of the 'curse of knowledge,' we couldn’t find common ground because we thought we just knew there wasn’t any.

Alda reminds us of the strange truce that spontaneously arose between German and British soldiers in the trenches during World War I. On Christmas Eve, some Brits heard Germans singing Christmas carols. Before long, “enemy” soldiers were trading schnapps, cigarettes, and chocolate. In some places, they played improvised soccer.

He concludes: 'If people are shooting at you repeatedly for months, and if reminding them you share something in common can silence the guns for a while, something important is going on.'

In other words, a connection.

Here’s looking at you."

--K. C. Cole

Close

Library Journal:

"Alda brings a distinct perspective with his trademark warmth and humor..."

Library Journal:

"Today, we have more ways to communicate than ever before, but how well are we actually communicating? As founder of the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University, the beloved actor and author helps researchers learn essential skills that can help them communicate their work to a wider audience. The center also trains health-care professionals, with the aim of improving their relationships with patients. It's not only scientific concepts that need clarification; the content of our daily lives can be better expressed and understood. Alda utilizes methods that he has learned at the center and through his work as an actor to explore how we can become better listeners and communicators. Drawing on a range of scientific and social science research, as well as his work in improvisation and directing, Alda outlines the steps and missteps in relating to other people in productive, meaningful ways. VERDICT Alda brings a distinct perspective with his trademark warmth and humor. As he addresses current popular themes in general nonfiction, readers can imagine his voice and expressions in recounting his experiences, making this book's content even more welcoming."

--Meagan Storey

Close

Publisher's Weekly:

"...he explains how improvisational games, empathy exercises, and storytelling tools can help anyone get better at communicating, listening, and relating everywhere 'from the boardroom to the bedroom.'..."

Publisher's Weekly:

"Veteran actor and director Alda (Things I Overheard While Talking to Myself) turns his attention to the world of social science in this breezy overview of work conducted at the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University in New York. Citing the center's research, he explains how improvisational games, empathy exercises, and storytelling tools can help anyone get better at communicating, listening, and relating everywhere 'from the boardroom to the bedroom.' Though widely associated with his role on the TV show MASH, Alda also hosted Scientific American Frontiers on PBS for 11 years, and he writes as enthusiastically about his experience with educational programming as he does about the scientists who teach the art of empathy to autistic children and medical doctors, among other subjects. Readers expecting healthy doses of Alda's signature dry wit, however, might be disappointed. Other than a riff about his dentist and the occasional throwaway joke, he's all business here."

Close

Booklist Reviews:

"This is an enlightening and thoughtful combination of shared experience and advice."

Booklist Reviews:

"Alda, known for his acting in shows like M*A*S*H and The West Wing, has been exploring his deep interest in the sciences for the last several decades, as the host of Scientific American Frontiers (which ended its 12-year run in 2015) and as the founder of the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science, at Stony Brook University. It is his work with the latter that Alda draws on, although this inquiry was in part inspired by his work with the series. Alda noticed when speaking with scientists that often their explanations went way over laypeople's heads; conversely, when he started his work on Scientific American Frontiers, his assumptions about his own knowledge hindered his dialogue with experts. Alda lays out how improv techniques such as mirroring can help improve communications skills, and he stresses how important active listening is to a successful conversation. He goes on to illustrate how essential these skills are in all walks of life, from motivating employees to reaching autistic children. This is an enlightening and thoughtful combination of shared experience and advice."

Close

PopDust.com:

"Alda takes great care in explaining the concepts he wants to share, and yet his prose never becomes overly ponderous...Alda has an excellent grasp of everything he discusses here. He cites scientists and studies easily to back up his hypotheses."

PopDust.com:

"Alan Alda will be known forever to the wider world as the iconic Hawkeye Pierce of M*A*S*H. However, in the last twenty or so years he has been an influential part of a quiet revolution in the scientific community. In his time as host and interviewer of Scientific American Frontiers he became fascinated with the art of science communication. When were the scientists he interviewed at their most relatable? When were they hiding behind jargon?

Through his background in acting and improvisation, he began to distill what he learned as an interviewer, factoring in the latest research on emotional empathy and theory of mind. This lead him to create the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University. Out of that came his new book, If I Understood You Would I Have This Look On My Face?, which is a fascinating compendium of everything he has learned. Part textbook, part memoir, part gentle conversation, Alda discusses concepts about theory of mind, empathy, and generally tries to make the world a better place through communication.

I was lucky enough, in tandem with reading the book, to attend Alda's accompanying talk at the May 12th Random House Open House. An excellent event, and one that I recommend to anyone with a fondness for reading. Comments and quotes from him in this article are from that event.

If you have read Alda's previous books, then his style of writing here will be familiar to you. It is the same tone he speaks in. Gentle, warmly patricianal, and never too far away from a joke. 'I can [see] what you're thinking,' he said ominously, referencing his newfound ability to read minds to the Random House audience, 'and it's that you love me.' He was not wrong, and laughter ensued.

As you might expect, given the topic of this book, Alda takes great care in explaining the concepts he wants to share, and yet his prose never becomes overly ponderous. With a book such as this one, it would have been so easy for it to be a dry, pseudoscientific tome, but If I Understood You is blessedly free of these trappings.

While you would never call this a scientific treatise (the jokes are too good), Alda has an excellent grasp of everything he discusses here. He cites scientists and studies easily to back up his hypotheses. Though this would not be enough for a peer-reviewed paper, for your average reader (myself included), this proves to be more than sufficient in opening up a new perspective on the art and science of communicating.

Alda inevitably brings many of his suppositions back to improv and acting exercises, which is to be expected given his background. He speaks in relation to 'relating', in which he quotes Mike Nichols, who once told him: "Relating isn't the icing on the cake… it is the cake," as he directed Alda in a play. "I thought relating just meant looking at someone, so I did," Alda demonstrates with an imaginary scene partner, "[then Nichols] said 'Relate more!!', so I did this," he leans in uncomfortably close to the imaginary actor, causing laughter in the crowd. Alda's process of listening and relating has obviously evolved somewhat since then.

Alda describes an exercise tested at the Stony Brook centre to improve empathy, where subjects, on a daily basis, were encouraged to notice people's facial expressions and assign them an emotion. Test subjects were found to be more empathetic on a standardized empathy test after a week of performing this activity on a daily basis. Alda speaking of his own experience with the technique said 'I think I would have been a better actor sooner, if I'd had this earlier,' adding, 'I find people less annoying now.'

Another exercise he details in depth is the classic actor mirroring exercise, in which one actor must copy another's movements exactly, like a mirror. He uses this as an analogue for communication, stating how listening is a two-person exercise. He demonstrated this at the Random House Open House using an audience volunteer. As he did so, he added: "It's my job to make her look good, and that's part of communication."

It is the job of a scientist explaining a theory, or anyone explaining anything, to ensure that the person they are communicating with can follow them. 'The idea is to make that contact [with people] habitual… it makes [people] more open, more human.' It will not surprise you that Alda is a very open person.

'We are social animals who are condemned to one another's company,' says Alda, speaking of the tribulations of communicating and relating. What makes this book so endearing is how genuine his fascination with the topic is. You never get the sense that he was bored at any point whilst writing this, and his enthusiasm is a contagion communicable through the text. 'It's not a formula,' says Alda, 'I'm looking for experiences that transform you in ways you can keep at it… it's not a formula, it's an improvisation.'

What started as his own quiet interest in science has evolved into an incredible hybridization of the fields of acting and scientific discourse. This work feels surprisingly overdue. It's not that these exercises will be new to actors, they won't be. And it's not that these concepts will be brand new to behavioral psychologists either. What's new here is the interdisciplinary application of these principles, and how accessible he is able to make them.

Alda's work could well improve scientific discourse the world over, and day-to-day interactions in general. As he recanted at his talk: 'one physicist said to me [about the work]: "This has saved my marriage".' Alda set out to improve scientists' people skills, and may have ended up with a blueprint for doing a lot more than that. Highly recommended for people of all stripes."

--Thomas Burns Scully

Close

PopMatters.com:

"... a rich meal that fulfills and makes us eager for another serving."

PopMatters.com:

"There is a difficult scene in the Introduction to this book that sets the basis for what will prove a rich, enjoyable, comfortable journey through the always troubling differences between interpretation and translation. Alda, who notes that he’s “well over fifty”, is in the operating chair in his dentist’s office, moments away from experiencing a procedure that will change his life. “There will be some tethering,” Alda is told. He asks for meaning and receives an impatient response from the dentist.

What he doesn’t know is that in order to fix what’s needed, the dentist decides to temporarily alter Alda’s face, turning what was normally seen as a smile into a sneer. The dentist had torn Alda’s frenum (the connective tissue between the gums above our front teeth and upper lip) without effectively communicating the details and consequences of the procedure:

'I’ve come to see my exchange with the dentist that day as something that happens frequently in life—a brief encounter that threatens a relationship’s delicate tissue, the tender frenum of friendship.'

Alda continues by noting that rather than looking for a friend that day, he simply wanted assurance that he was being seen, that he was being recognized and understood. It’s a strong way to open what proves to be a compelling, enjoyable book by a man looking only for answers and understanding that the best way to get them is by drawing from minds more scientifically focused than his. He notes in the book that for the past 20 years he has been trying to determine why communication seems to be so hard, what obstacles have always been in our way. His work as host and audience guide for the PBS-TV show Scientific American from 1993-2004 took interesting routes to reach the same conclusion: Who are we? Why are we here? What’s the biggest obstacle preventing full understanding between medical practitioners and patients?

Alda is perhaps best known as Benjamin Franklin “Hawkeye” Pierce in the classic CBS-TV series based on the 1970 Robert Altman film M*A*S*H. Hawkeye was an acerbic surgeon who found himself in the Korean conflict against his will patching up wounded soldiers, trying to save them, and otherwise searching for a way out. In the nearly 35 years since the end of that show’s 1972-1983 run (eight years longer than the actual Korean War), Alda has built an interesting film career building both on the comic, empathic persona of Hawkeye and also some purely diabolical characters. With his Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University, Alda has built a strong, legitimate track record as a journeyman scientist, and it’s that voice he carries throughout this book that makes the trip well worth taking.

There are two sections in this book sliced into various chapters. In the first section, “Relating Is Everything”, Alda focuses on what he knows best, theater and improvisation. How this will work with the average reader depends entirely on their tolerance for theatrics, which by their very definition can sometimes be too precious. For those of us willing to take the journey, though, Alda’s excitement is palpable. He makes us want to participate. For instance, of the skill known as “Responsive Listening” he notes: “You don’t say your next line because it’s in the script. You say it because the other person has behaved in a way that makes you say it.” This leads him to wonder whether scientists could become more personable and available if they studied the art of improvisation.

The excitement Alda expresses in this book is tantamount to child-like wonder, and that’s risky for a book that may seem to be wandering if a more conventionally science-minded reader wants something serious. “Improvising transforms you,” he writes, “But it does so over time.” In “The Heart and Head of Communication”, Alda goes back to Thomas Jefferson’s “Dialogue between Head and Heart”. This 1786 letter Jefferson wrote to a desired paramour expressed for Alda the essence of clear communication. We have to decidedly understand what the other person is thinking, perhaps even learn how to forecast their reactions through body language and tone of voice. Understand what the other person is feeling, develop a clear awareness of what (and how) they are thinking, and some sort of fulfillment will take place.

Alda continues by looking at “The Mirror Exercise”, which is nothing but what its title suggests. Two people stand before each other, make synchronous movements, and they try to match. The goal of synchronous unity in heart and mind cannot take place without clear observation. Note the use of clear (clarity) rather than perfect. Unity takes time. “There’s no pretending in improvising,” he notes, “no deciding to behave differently.” It’s this aim towards fully understanding the here and now, the present moment, which makes this book so compelling and emotionally valid.

There are many heroes in this book, and Alda generously gives them space to tell their stories. Massachusetts General psychiatrist Helen Riess speaks about a life-changing moment where a woman who appeared on her surface to be fully confident was in fact (as seen by detectors attached to her skin) extremely anxious. “Examining the spikes in the patient’s emotions, she could see the woman was having ‘these little leaks’…leaks of emotions that didn’t necessarily show on her face. ‘She was very good at concealing them’ (Weiss notes.) Dr. Matt Lerner discusses Cognitive and Affective Empathy and the Autistic Spectrum. He adapted improvisatory games originally intended for actors and applied them towards an autistic population. His goal, to help even the severely autistic mind read the actions and motivations of others, bloomed in a camp setting called Project Spotlight, serving over 350 people a year in the Boston area alone.

Alda brings Daniel Goleman’s “Emotional Intelligence” into his argument by condensing the latter’s steps: develop a primal awareness of the other (empathy), grasp their feelings and thoughts (Theory of Mind), and finally just learn how to understand complicated situations. Alda seems to be bringing these previous studies in less as filler for this book than basically providing the foundation for something bigger. Is he breaking any new ground here? No. What he’s doing is looking at ideas like “Affective Resonance”, which Helen Riess notes is “…the feeling of connectedness we’re able to get with other people…” Later, Alda introduces Evonne Kaplan-Liss, a doctor who argues (as Alda sees it) that 'Words can introduce you to an idea, but we think it takes an experience to transform you.'

In Part Two of “If I Understood you…” titled “Getting Better at Reading Others”, Alda enters as a lab rat, and this part of his narrative is particularly entertaining. He wants to learn how to name emotions as a way to separately deal with them. It’s the idea of determining how well we look at each other, how closely we understand visual cues, and Alda clearly wants to understand the success rate. No matter how highly experiment participants score in learning to read others, they will always score higher when they pay attention to emotions and faces.

For all that is bright and hopeful about empathy, there will always be dark and hopeless. In “Dark Empathy”, Alda recounts the classic 1975 experiment by Al Bandura, in which participants gave a greater electrical shocks to other participants they had heard referred to as animals. Also, “Reports have come out of Guantanomo that psychologists have advised jailers there on how to make their prisoners feel helpless…” From the darkness of big pharmaceutical companies and the American Psychiatric Association conspiring to control emotions through controlled doses, the bad sides are everywhere. To his credit, Alda’s goal is positive inquiry but he does not hesitate to shine a light on the darkness.

In “Reading the Mind of the Reader”, Alda looks at the need to help science students distill and clarify their written narratives as effectively as their spoken trains of thought. Of his experiences at his Stony Brook center, he notes: “The more we reinforced our students’ ability to focus on the other person, the better able they were to express themselves with words that would land on the reader with clarity.” Again, Alda notes that the initial imposition of improvisatory techniques into written activity (a freewriting exercise to open the mind) was helpful for the overall clear flow of ideas between communicators.

In “Story and the Brain”, Alda goes back to the clearest basic fundamentals and discusses Aristotle and the building blocks of the story. For Christine O’Connell, an Instructor at his Center, it breaks down as follows, to be read in the following order: question, suspense, turning point, and resolution. This is a more distilled version of the diagram used in Literature classes: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, resolution. Whether for the concrete objectivity of science purposes, or the more subjective high-mindedness of creative literature, it all works. Communication is about overcoming struggle and answering questions.

By the end of his book, Alda looks at “Jargon and the Curse of Knowledge”. It’s an apt way to finish a swift and enjoyable journey through the mission of finding verifiable evidence to life’s questions. There’s good jargon (science speak) and there’s bad, but “When a scientist uses language that’s just beyond the audience’s reach… or when a doctor describes a medical procedure in terms the average patient doesn’t understand… [they] hear the melody but the people listening only hear the tapping…” For Alda, the essence of nature is a beautiful song, not just melody and rhythm. “I want to be cautious and not regard these… as the last word in understanding human interactions,” Alda notes earlier in the book. “One thing you can say for sure… is that they leave you with the suggestion to do more studies.”

Alda’s book is neither the first word nor the last word in a layman’s journey through scientific inquiry. It is, however, a rich meal that fulfills and makes us eager for another serving."

Close

CompulsiveReader.com:

"The title ...reflects an intellectual sensibility conveyed clearly and directly. It underscores the very points he is trying to make in this book. Alda has a gift for speaking about lofty ideas in layman’s terms, and his fervor for his subject matter shines through. This passion is at the heart of what engages us."

CompulsiveReadercom:

"Most of us know Alan Alda as an award-winning actor, particularly from his eleven seasons on the hit television series M.A.S.H. As Captain Hawkeye Pierce, he perfected the double entendre and danced a fine line between humor and tragedy. He not only entertained us, he touched our hearts and enlightened our minds. Now in his ninth decade, he shows no signs of slowing down his penchant for inquiry. It is a testament to his longevity on multiple levels. In many ways he is our “everyman”—someone with fame, accomplishments and recognition but also someone we feel comfortable with, who understands how we feel. He’s smart but approachable and speaks our language.

A life-long interest in science led Alda to engage with various renowned scientists and scientific organizations. This included hosting the acclaimed PBS series “Scientific American Frontiers” that also aired for eleven years. He has played a physicist on Broadway and authored the play Radiance: The Passion of Marie Curie. He was named a fellow of the American Physical Society in 2014 for his work helping scientists with communication skills. These converging interests led him to establish the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University in Long Island, New York where he is also a Visiting Professor. It was inevitable that his experience in the entertainment field and quest for scientific knowledge would coalesce. The beauty of it is that Alda is able to share his expertise with us in colloquial, available ways. This sharing is at the crux of his intentions in both fields: communication and relating. The title to his newest and third book, If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look on My Face? and its subtitle, “My Adventures in the Art and Science of Relating and Communicating” reflects an intellectual sensibility conveyed clearly and directly. It underscores the very points he is trying to make in this book. Alda has a gift for speaking about lofty ideas in layman’s terms, and his fervor for his subject matter shines through. This passion is at the heart of what engages us.

Alda examines communication in all aspects of life. The lynchpin is the word “relatable.” It is at the heart of compassion that allows us to truly recognize another person and connect with them. Alda often illustrates his points with personal stories and references that bring a universal appeal to his intentions. During his initial foray as host of “Scientific American Frontiers” he blunders through an early interview and learns one should listen with eyes, ears and feelings. As he states, “I hadn’t been listening in three different ways” (P. 6, l. 5). There is a misconstrued assumption that we know where a person is coming from before they actually tell us anything. We need to watch body language and keep all our senses alert. These realizations lead Alda back to his earliest days as an actor and the key ingredients of improvisation and “spontaneous interactions” (P. 6, l. 26). Those exercises created more immediate and genuine responses in connecting with other actors and, certainly, this would correspond to its potential in all relationships. But we have to be vigilant in keeping these connections alive. Alda observes: “But it seemed to be something I had constantly to relearn” (P. 9, ll. 8-9). Perhaps the basic human condition of fear precludes us from implementing these skillsets permanently into our psyche and behaviors. What are the defensive and resistant places we act from in relating to another person? We listen but are often ready to defend, deny or rebut. When do we truly hear, and possibly change, when we are always confronting those sentries of resistance and misunderstanding that stand guard at the doorways to communication? The challenge is to continue to relate openly with true intentions by examining old wounds that intrude upon the process if they remain unexamined and unhealed. These are habits and behaviors instilled in us from our original caregivers and role models. This is one aspect of relating that needs to be given greater priority and consideration when analyzing how all of this really works.

One of the ways Alda confronted communication issues was in his acting career. He realized that “You don’t say your next line simply because it’s in the script. You say it because the other person has behaved in a way that makes you say it” (P. 10, ll. 12-14). There is an active, almost spiritual impetus to live in the moment without the intrusion of anticipatory responses and actions. Perhaps the missing component is those personal wounds, learned behaviors and fears that preclude us from consistently breaking through those barriers. Alda approaches these situations through the dynamic of training. Listening is not enough. As he observes: “I’ve been listening to good pianists all my life and I still can’t play the piano” (P. 20, ll. 7-8). With his legendary good humor, he continues to blend homespun comedic references with serious concerns and applications lending to an easy flow of the text.

Another significant component is empathy. What creates an empathic connection? Alda leads us to the concept of the story as a critical component of conveying messages and communicating with one another. In pondering this, I recalled reading at a poetry event for my newly released book, hoping to generate interest for sales at the conclusion. When reading one particular poem about childhood abuse, I became very emotional. The poem came across as a story about the people and places and how things felt during that time. One man came up to me afterwards and bought a book. As I signed it he told me he hadn’t really planned to buy it until he heard the story and attendant emotion in my voice. He had not experienced a similar situation, but he felt empathy for times he had similar feelings. This is the axis of connection and pertains to Alda’s reference of Daniel Goleman’s work on emotional intelligence and social awareness. Goleman posits three separate steps: “…having an instantaneous, primal awareness of another’s inner state (empathy); then, grasping their feelings and thoughts (Theory of Mind); and, finally, understanding” (P. 77, ll. 11-14).

In a section about couples and active listening, Alda discusses the petty annoyances that preclude true interactions. His notes that “…little irritations tend to mount up, but what I’m hearing from researchers…a richer kind of listening can produce a little cooperation and a lot less friction” (P. 79, ll. 3-5). As an example, couples sharing household and other responsibilities equally have less stressful relationships, and usually more sex as well. I’m sure this works on a practical level. But what would happen if those couples plunged even deeper into those petty irritations and why they weren’t working together. Again it goes back to childhood, early modeling behaviors and how we seek to resolve those in partnerships throughout our lives. All relationships reflect many things back to us that are immensely helpful if we can move beyond the blame and shame game. As in the teachings of someone like John Bradshaw, any person we come into contact with can act as a mirror for our own awareness and growth. This brings us back to Alda’s advocacy for improvisation. Working without a script leaves us vulnerable in a good way and open to alternate results, not just the consequences we already anticipate.

Alda also discusses how to work on these issues on our own. It makes sense that we won’t be able to read others very well if we can’t understand ourselves. He spends considerable time observing people’s expressions that, in turn, lead him to guess at the emotion behind the visage. He concludes “…naming other people’s emotions seemed to help me focus on them more and it made talking to them more pleasant” (P. 107-108, ll. 32, ll. 1-2). We learn about someone by actively listening. Still, we need the right tools and attitude to be able to do so. His story of a young man who worked with autistic children illustrated that understanding emotions and making that empathic connection went a lot further than practicing rote exercises.

Mr. Alda offers a lot of scientific experiments to support his journey into the various studies of communication and human relations. He had to remain open to the possibility that not all studies would lead to the conclusions he sought. While awaiting the results of one study, he anticipates a possibly disappointing outcome and notes with his signature humor: “…I took comfort in the idea that I would be able to write an account of an experiment that took an interesting hypothesis and proved it wrong. This would be a helpful thing to do. It would be a service to mankind. In other words, I was slightly depressed” (P. 114, ll. 24-28). In reality most of the experiments supporting evidence of our inter-connectedness offered positive reinforcement.

As writers we need to engage our readers from the very first sentence. This involves focus and clarity. Alda quotes a paper written by George Gopen and Judith Swan, “The Science of Scientific Writing,” that is applicable for any kind of writer: “Readers expect [a sentence] to be a story about whoever shows up first” (P. 137, ll. 9-10). In other words, parse the verbosity and enlist the reader’s interest from the beginning. Gopen posits further that the end of a sentence is vital and “…calls it the stress position, a place of emphasis” (P. 137, ll. 20-21). Alda compares it to the punch line of a joke. But it all speaks to proper communication. And Alda is interested in yoking the divide between science and art in ways that not only illustrate how closely they are related but how they highlight our interconnectedness as people. He demonstrates this beautifully with the story of The Flame Challenge. Children and adults from around the world sent entries on how to best explain the nature of a flame. A last minute entry by university student Benjamin Ames engaged everyone on multiple levels: information, wonderful visuals and an ear-catching song. An improvisation to teach and inform became an example of excellent communication.

Perhaps the best foundation for communicating is examination of oneself. As Alda states: “…by connecting to your self you can connect to your audience” (P. 152, ll. 5-6). We need to be in touch with our own emotions because, as Alda further notes, “…emotion helps us remember” (P. 157, l. 11), and an important link to this can be stress. A stressful experience is an impressionable reminder. But a negative link between memory and stress is not the only avenue to emotion, as Alda reminds us. Laughter works just as well and goes further to engage people in positive ways.

We all need to overcome obstacles, which is at the heart of dramatic action. Challenges are opportunities to understanding, to becoming better people. We need to be passionate about our intentions, keep our commonalities in mind and maintain awareness of the self before we can communicate properly with another. We need to embrace the gifts of failure and keep clear on basics. Alda emphasizes similarities as common denominators, observing that we “…have to be aware we’re alike” (P. 181, ll. 26-27). Perhaps the greatest ingredient at the heart of communication is caring. Mr. Alda has never been lacking in that department, and this latest book confirms that."

Close

Vital Magazine:

"It is a good feeling, and such an elusive one for many of us lately that Alda’s bestselling meditation on the art of communication, as well as some of the science behind it, might just be the ideal book for our hyper-partisan moment."

Vital Magazine:

"A 2012 study conducted on behalf of Bosch home appliances found that over 40 percent of Americans admitted to having fought with a family member over the correct way to load a dishwasher. This is not one of our prouder national statistics, but according to Alan Alda, it’s one that probably shouldn’t surprise us. As he explains in his new book, 'Pretty much everybody misunderstands everybody else. Maybe not all the time, and not totally, but just enough to seriously mess things up.'